What lessons to take from farmer-labor parties?

, editor of the International Socialist Review, looks at the fate of farmer-labor movements in the early 20th century, in response to an article in Jacobin.

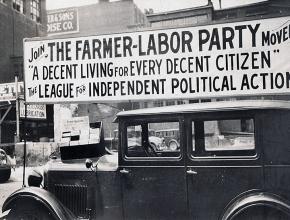

LAST DECEMBER, Jacobin published an article by Eric Blanc titled "The Ballot and the Break," tracing some of the little-known history of Minnesota's Farmer-Labor Party (MFLP), which, he writes, "built a mass base in the 1920s and captured the highest levels of state office in the 1930s."

Blanc explains that his main purpose for writing the article is to criticize both those who argue for the left to work on "realignment" within the Democratic Party and those who argue for a "clean break" from the Democrats and Republicans on the grounds that "any involvement within capitalist parties [is] an unprincipled dead end."

He introduces his subject by explaining that he had embarked on his research expecting that it would vindicate the "clean break" position, only to discover that the example of the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party and the Non-Partisan League (NPL) in North Dakota proved to him that:

the tactics deployed in founding the Farmer-Labor Party challenge the orientations of both major poles in the debate. To my surprise, I found that the Minnesota experience demonstrates the potential viability of what I would call a "dirty break" approach: the use of Democratic and Republican ballot lines to implode the two-party system.

It is clear, then, that Blanc's history lesson serves contemporary purposes--to prove that working within the Democratic Party to "implode it from within" is a viable tactic for the left today.

The problem is that he not only fails to show historically the viability of this "tactic" in the early 20th century. He fails to prove how, or in what way, it could be effectively used today.

There was a brief historical window in which farmer and farmer-labor movements were able, in a few states, to engage in what were, in effect, hostile takeovers of Republican and Democratic primaries. But this avenue was already no longer an option by the end of the period he discusses--let alone possible in today's conditions.

Re-viewing the History

The NPL and the MFLP did not enter Republican and Democratic primaries in the 1910s and '20s as a "tactic," as Blanc writes, but as a part of political strategy.

In North Dakota, the aim of the NPL wasn't to form a third party. It, in fact, counterposed its hostile takeover strategy to the idea of forming a third party (hence the name "non-partisan"). The anti-third party idea that informed much non-partisan thinking was expressed by Edward F. Keating, writing in Labor, the weekly paper of the railway unions, in a debate where he took the side against forming a labor party:

The primary law renders the formation of new parties unnecessary for the reason that whenever the people wish to renovate one or both of the old parties they may do so by the simple expedient of taking advantage of the primary.

However, thwarted at every turn by the two main parties, this strategy encountered strong obstacles by the early 1920s. As historian Michael Lansing notes:

Frightened by the establishment of state-run industries in North Dakota and the League's control of government there, party politicians across the West sprang into action. They immediately began proposing modifications to primary law in states where the NPL threatened their hold on power. It proved the most effective way to reaffirm partisanship and defeat the League.

Wherever the NPL/farmer-labor movement in various states gained traction and tried to take over (mostly Republican, but also Democratic) primaries, the two main parties joined forces and formed alliances--with the support of the wealthiest citizens--to defeat it; and wherever that happened, the NPL's were compelled by circumstance to act like third parties. As historian Nathan Fine wrote:

In 1918 and 1920, the Democrats and Republicans combined to oppose the league in North Dakota, thus putting the organization into the position of being a party whether they liked it or not.

Once the league failed to win at the primaries it did not support the victor, the choice of the party voters, it bolted. And when the league captured the Republican Party primaries, those opposed to its domination left the Grand Old Party and combined with the Democrats to defeat it at the election, which followed the primaries. The league was a party in spite of itself, in spite of its supposed nonpartisanship, and in spite of its pretense of entering the primaries.

The movement in North Dakota--after taking control of all sections of the state government except the Senate, in 1919--collapsed in a matter of years under the weight of factionalism, a successful bipartisan recall movement and a "boycott of North Dakota bonds in national capital markets," according to historian Richard M. Valelly.

By 1921, the North Dakota Non-Partisan League had become a progressive club inside the state Republican Party.

The Minnesota Farmer-Labor Movement and What It Shows

As Blanc notes, the farmer-labor movement in Minnesota was, from the beginning, divided between its farmer and labor wings over whether to move toward a third party or continue to "bore from within."

The movement in its first few elections was able to gain a political foothold by invading the Republican primaries and pushing its own candidates. This strategy did not, however, cause the other two parties to "implode"; rather, it led to a move by the Republicans to shut the door on this strategy.

When the Farmer-Labor Party, using this strategy, failed to secure victory for enough of its candidates in the 1922 primary, it fielded its own candidates directly in the general election. This prompted the Republicans to pass a "sorehead" rule outlawing parties from running their own candidates if they participate in the primary of another party.

This effectively removed the "bore from within" strategy from the table and accelerated the debate in the FLP. The labor section led by William Mahoney was able to establish the Farmer Labor Association. From here on, it ran its own primaries and fielded its own candidates as a third party.

According to Blanc, NPL leader A.C. Townley's insistence on "nonpartisanship" opened him up to supporting fusion with Republicans. "Had there not been a sufficiently principled and influential political current willing to push back against these intense external and internal pressures," writes Blanc, "the farmer-labor movement would have been absorbed back into the two-party system in 1922."

This can hardly be described as a "dirty break," as Blanc uses the phrase, because it implies that entering the Republican primaries was a deliberate tactic employed by the NPL as a means to build up forces for a "break" to create a third party--whereas the NPL viewed entering the Republican (and in some states, Democratic) primaries as the sole and sufficient means to politically represent farmers.

The whole point of the NPL's non-partisan policy was to try to win the vote of farmers--by promoting policies in their interests--without requiring that they break from either of the two main parties. In Minnesota, that strategy had to be overcome by Mahoney's labor wing to form the Farmer-Labor Association and maintain the movement's independence.

To back up his "dirty break" position, Blanc favorably quotes a historian who argues that if the NPL "had adopted third-party tactics at the outset, it could not have won its first electoral battle." This begs the questions as to the purpose for which socialists engage in electoral work--and ignores the electoral successes of the Socialist Party.

Blanc acknowledges the role of socialists in the FLP and the success of Thomas Van Lear in his run for mayor of Minneapolis in 1916, but he doesn't mention the electoral success of the Socialist Party (SP) in this period overall--perhaps because it offers plenty of examples of what was possible without entering Republican or Democratic primaries.

Though the SP leadership was at this stage quite moderate, it faced severe repression for its official antiwar stance, contrary to the MFLP, whose official stance was pro-war. This seemed, however, to boost the SP's electoral support in the working class.

In November 1917, the SP won seven mayoral races in major cities and received anywhere from 20 percent to more than 50 percent of the vote in local elections in a dozen of Ohio's largest cities, 10 cities and towns in Pennsylvania, and six cities in Indiana. It got 34 percent of the vote in Chicago and was only defeated due to the Republicans and Democrats uniting behind a single slate. SP leader Morris Hillquit won 21.7 percent of the vote New York City's mayoral race in a field of five candidates.

In other words, one could just as easily point to these SP electoral successes--rather than those of the early "bore from within" Farmer-Laborites--to show that independent politics had some real legs in this period.

Measured by how many public offices are won, the biggest success of the Farmer-Labor movement is the North Dakota NPL, which seized both houses and the governorship before its recall.

But should socialists measure success by whether or not we win governorships and other governmental offices--where socialists become subject to the inevitable pressures of running a capitalist state--or do we measure success by how election campaigns and winning legislative positions help us to advance our struggle overall?

Blanc has forgotten the ABCs of Marxism on parliamentary elections: "Even when there is no prospect whatsoever of their being elected, the workers must put up their own candidates in order to preserve their independence, to count their forces, and to bring before the public their revolutionary attitude and party standpoint," Marx and Engels wrote.

Of course, this does not mean that we should be indifferent to how many votes we can get. But at the same time, we view votes as a useful, if imperfect, barometer of the state of class consciousness and the level of support for socialist politics, not as a road to power.

In his desire to extol the virtues of the "dirty break," moreover, Blanc glosses over a number of important political observations that would seem natural for a revolutionary socialist to make about the limitations of the Farmer-Labor movements.

He mentions, for example, the extreme repression faced by the early League. Left out, however, is any explanation of the character of the ideological assault on the movement or its response. Attacked by its opponents for its alleged disloyalty toward the war effort and for being "socialist," the League spent a great deal of energy attempting to prove that it was not disloyal, even going so far as selling war bonds at mass campaign rallies, and insisting in its propaganda that it was not socialist.

Looking at the Bigger Picture

BECAUSE OF his narrow aim of showing that "bore from within" tactics worked, and could work again, Blanc fails to acknowledge bigger--and to my mind, much more important--lessons of this era that cannot be understood without taking the trajectory of these movements into account from their beginning in the 1910s to the final fusion of the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party with the Democrats in 1944.

Of particular importance is the relationship between the MFLP and Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal.

Though Blanc's article is largely focused on the 1920s, it gives prominence to Floyd B. Olson--his picture graces the Jacobin web page featuring the article--who was twice elected Minnesota governor on the Farmer-Labor ticket (in 1930 and 1934).

The article mentions obliquely, in a passage extolling Olson's successful social reforms, that under his watch, "relations with militant workers were rocky during the 1934 'Teamsters' Rebellion.'"

These "rocky" relations consisted of Olson declaring martial law and bringing in 4,000 National Guard troops into Minneapolis; banning picketing, but allowing trucks issued with military permits to operate; and finally using National Guard troops to raid Teamster headquarters and arrest many of the strike's leaders in order to pressure them to settle. Their release was only secured by a mass march of strikers the next day.

Olson found himself in a contradictory position. In the words of Trotskyist leader James Cannon, he was, on the one hand:

a representative of the workers; on the other hand, he was a governor of a bourgeois state, afraid of public opinion and afraid of the employers. He was caught in a squeeze between his obligation to do something, or appear to do something, for the workers and his fear of letting the strike get out of bounds.

Given this history, one would think that Blanc would have more to say than this passing remark: "The strengths and weaknesses of the FLP in power were not unlike those of social-democratic administrations elsewhere in the world."

But the problems go beyond this: Olson was most responsible in the 1930s for wedding the Farmer-Labor Party--with the help of newly arrived Communist Party organizers and activists and the use of patronage to create his own political machine--to Roosevelt and the Democratic Party.

This is especially important given that the period of the mid-1930s represented another high point of interest in the working class for its own political party--a history that is as "widely ignored" as the Farmer-Labor period that Blanc highlights.

The resurgence of interest in forming labor parties in the 1930s coincided, as it had previously, with not only a deep economic crisis, but also a substantial increase in strikes, which flared up in 1934 to involve more than a million workers.

As historian Eric Leif Devin notes regarding workers' reaction to the bloody defeat of the strike by the United Textile Workers (UTW) union that raged across the Eastern seaboard in 1934: "In both the South and New England, the United Textile Workers' strike taught mill workers to distrust the Democratic Party, whose representatives had fought the strike." UTW President Frank Gorman was a leading proponent of a labor party in this period.

Labor leaders like Sidney Hillman and John L. Lewis embarked on a systematic campaign to kill the labor party movement and ensure that labor remained in Roosevelt's camp. The policies of Farmer-Labor Governor Olson also thwarted this promising but brief movement and played a role directing it back into the channels of the Democratic Party. As historian John Earl Haynes writes:

The Farmer-Labor Association maintained close links with the Roosevelt administration, an association that Governor Olson had initiated. In 1932 the nation's economic crisis was approaching catastrophe, and Olson saw Roosevelt's election as the most likely way to bring about federal action. The governor appeared with Roosevelt during a campaign stop in Minnesota and discouraged attempts to commit the Farmer-Labor Association to a third-party presidential ticket.

After the election Roosevelt respectfully listened to Olson's suggestions for federal legislation to relieve farm bankruptcy and urban unemployment; Olson, for his part, endorsed most of the President's legislative programs. Roosevelt consulted Olson on federal patronage decisions, and the governor included cooperative Democrats in the distribution of state jobs. By 1936, the political understanding between the two had evolved into a firm, although informal, alliance.

When Olson died suddenly in 1936, Minnesota Democrats agreed to a quid pro quo to refrain from opposing Elmer Benson, the FLP's candidate in a special election, in return for Farmer-Labor support of Roosevelt. Roosevelt openly endorsed Benson when visiting Minnesota, and in return, Benson declared his support for the New Deal.

When the Communist Party shifted in 1935 to the Popular Front, it also threw its weight behind the New Deal. It dropped its opposition to the Farmer-Labor Party and entered it as a loyal ally of Olson. Again quoting Haynes:

Communists became a distinctly moderate force in the Farmer-Labor Association, shunning class conflict politics and urging Farmer-Laborites to avoid radical rhetoric. Communists encouraged the expansion of the Farmer-Labor Movement to include middle-class professionals and small businessmen in addition to workers and farmers; in fact, they welcomed anyone sympathetic to the New Deal who was willing to cooperate. This Communist policy coincided with the view of the Farmer-Labor party's moderate wing that the movement's radical goals should be dropped for the moderate liberalism of Roosevelt's New Deal.

Farrell Dobbs, a member of the Socialist Workers Party and a leading participant in the Minneapolis Teamsters strike in 1934, offered this assessment of the Minnesota FLP in the 1930s:

Programmatically, the FLP fell far short of being a party of the kind the workers needed. Its basic line centered on a call for reforms under the existing system to be achieved in a gradual and orderly manner through parliamentary action alone. Emphasis was placed accordingly on the substitution of reformist politics for class struggle actions. As interpreted by FLP representatives in public office, implementation of that policy required blocs with liberal capitalist politicians on a statewide scale, along with support of the Roosevelt Democrats nationally.

The Non-Partisan Con of the 1930s

In the early stages of the NPLs, the "bore from within" strategy was deployed by organized forces that were relatively independent, and highly critical, of both parties--with some degree of success in several cases.

In the 1930s, the unions set up Labor's Non-Partisan League (LNPL). But this was created for an entirely different purpose. In the words of historian Eric Leif Davin, the LNPL was "designed by its top leaders to be a transitional step toward...complete alignment of organized labor with the Democrats."

The creation of the LNPL allowed those who wanted to channel union support into the Democratic Party and quash the labor party movement to do so under the guise of preserving some semblance of independence, while those who wanted a labor party could rest assured that the chances for such a party still existed--at some future date. Meanwhile, those on the fence--worried about spoiling Roosevelt's chances, but sympathetic to the labor party idea--could hold a contradictory stance.

The arguments used by CIO leaders like Sidney Hillman and John L. Lewis to turn their union executives in favor of backing Roosevelt in 1936 and away from independent labor politics was that the stark choice that year was between two poles: either Roosevelt or fascism--a line also being pushed by the Communist Party.

In short, if the early Farmer-Labor represented an incipient third-party movement moving in the direction of establishing a third party, in 1936, Labor's Non-Partisan League represented--indeed, was designed deliberately as--a kind of non-partisan politics transitioning into alignment with the Democratic Party and away from the creation of a labor party.

Surely this historical lesson, and not the FLP's "dirty break," is far more relevant to the situation faced by the left today, when Bernie Sanders has set himself up as the man who will "transform" the Democratic Party.

Another important difference between today and the period of the 1920s and '30s is the state of the class struggle. The context out of which labor and farmer-labor parties in the late 1910s and 1920s emerged in the United States was one of rising class struggle unprecedented in scope.

As historian Robert Montgomery explains, "For the seven years following 1915, the ratio of strikers to all industrial and service employees remained constantly on a par with the more famous strike years of 1934 and 1937. The declaration of war had only a minor impact on this militancy." In each year from 1916 to 1922, more than a million workers struck--peaking at more than 4.2 million in 1919.

The period was also one of great growth in union membership, as Blanc points out. Between 1914 and 1919, half or more of Minnesota's industrial workforce became unionized, with union membership increasing from around 37,000 workers in 1914 to 89,000 workers in 1919--a 240 percent increase.

The very different circumstances today have to be borne in mind.

Today's "Dirty Break"?

Though "fraught with dangers," writes Blanc, "[t]he FLP's founding ...illustrates the potential of what I call 'dirty break' politics"--which he also presents as one means to end "the socialist movement's marginalization."

As to whether such a strategy could work today, Blanc concludes that it's "hard to say," but "it's conceivable that experiments with dirty break tactics could help both to regenerate a fighting labor movement and restore an influential socialist Left."

Today, however, social and political conditions are very different. The class struggle is at a historic low. The two-party system has been entrenched for decades, and the parties have a myriad of ways to thwart attempts to meddle from within or form third-party attempts from without. And while large numbers have expressed a greater openness toward "socialism" and many support Bernie's "revolution," Sanders' entirely unrealistic aim is to change the Democratic Party from within.

Many Jacobin readers might logically see Eric Blanc's arguments about the "dirty break" as of a piece with Jacobin editor Seth Ackerman's argument that socialists can create a path toward independent politics by skillfully exploiting Democratic Party ballot lines.

But there is no analogous organization to the NPL or the FLP today. The Democratic Socialists of America--which is much smaller--does not have an agreed-upon strategy of utilizing Democratic Party ballot lines as a tactical maneuver to build up forces for an independent political party that competes with the Democrats. Moreover, the two-party system is so "sewn up" that the maneuvers used by the MFLP in the early 1920s would not be possible today.

The same political roadblocks facing independent parties affect left-wing individuals and organizations attempting to use mainstream party ballot lines. Those attempting to utilize whatever loopholes they can to engage in elections within the Democratic Party will quickly find such openings closed off, just as soon as the Democrats realize what is taking place. The party will accept only such "progressives" that give the party a left veneer without actually challenging it.

Ackerman's proposal is not a realistic strategy for building a left party independent of it--and the problem with Blanc's article is that it seems to provide ammunition for Ackerman's fundamentally flawed case for radicals operating within the Democratic Party.

In the end, we must conclude that Eric Blanc fails to prove that, to use his own words, "any involvement within capitalist parties" isn't "an unprincipled dead end."