When Greece-style austerity spreads West

explains why the politics of austerity continue to endure more than five years after the official end of the Great Recession.

THE U.S. economy continues to expand according to official statistics, but the drive to shrink federal, state and local government continues, with attacks on public-sector workers' pensions, privatization of government operations and a relentless squeeze on social services.

With looming Greek-style debt crises in Illinois and Puerto Rico grabbing headlines, big capitalists and the politicians who front for them are attempting to set dangerous new precedents in an effort to shred what remains of an already minimal welfare state in the U.S.

The impact of those measures would be devastating: enormous cuts in education and health spending in Puerto Rico; the gutting of public education in Chicago; and cuts in pensions for state workers across Illinois. While the push for cuts in social spending and government services doesn't approach the catastrophic levels that Greece has endured, the underlying agenda is the same: a drastic and permanent cut in the standard of living for working people.

The politicians who pursue these measures are carrying out the interests of big corporations that have, for more than 30 years, hammered unions, outsourced jobs, held down wages and demanded higher productivity. Theirs is a long-term perspective based on making the U.S. a union-free, low-wage, high-productivity economy that can compete not only with traditional rivals in Europe and Japan, but also China and other newly industrialized countries.

The U.S.'s counterparts are determined to do likewise—hence Germany's determination to make an example of Greece by using European institutions to override national sovereignty and impose extreme austerity measures. Mainstream political parties—conservative, liberal and social democratic—have all furthered this agenda.

Given the scope and scale of these attacks, they cannot be resisted on a case-by-case, issue-by-issue basis. Instead, they have to be fought as part of a general resistance, challenging both the politicians who pursue austerity and the social forces driving the agenda. If Greece is an experiment in how far austerity policies can be pushed despite overwhelming opposition, it's also a model of social resistance that can be adopted around the world.

In the U.S., this struggle will necessarily involve a challenge to racism—from police violence to institutional discrimination—as well as sexism, homophobia and anti-immigrant policies that all flourish in an environment in which wealth inequality in the U.S. is at its highest level since 1913. That's why activists from the 2011 Occupy protest to today's Black Lives Matter movement have raised broad questions about inequality, exploitation and oppression.

WHAT'S AT issue—from Greece to the U.S. and beyond—isn't a passing budget shortfall during hard times. Rather, the austerity agenda is part of a systematic effort to destroy the post-Second World War social consensus in the advanced countries of Europe, the U.S. and Japan, and revive 19th century-style "liberal" capitalism.

That’s liberal, not in the political sense of the word, but how it is applied to the economy to justify the unfettered play of the free market—hence, the use of the term "neoliberalism" on the left today to refer to prevailing economic policies.

Neoliberalism's usual accomplice is austerity—a word often used in the news media, but seldom defined. According to Merriam-Webster's online dictionary, austerity is "a situation in which there is not much money and it is spent only on things that are necessary."

There are two flaws with this definition, at least when it comes to public policy. The first is the question of what is "necessary" social spending. The answer is different for, say, a hedge fund manager investing in government bonds and a single mother waiting an hour for a late-night bus so she can go to work, while her cousin looks after her child.

Certainly, the idea that there "is not much money" is also absurd in view of the $17 trillion Gross Domestic Product (GDP) generated in the U.S. each year, or the European Union's $18 trillion economic output.

The problem is that the money is increasingly concentrated in private hands or the military, rather than the state entities responsible for basic services such as education, health and state pensions (Social Security, in U.S. terms). In the U.S., government spending as a percentage of GDP fell dramatically during the Democratic administration of Bill Clinton, in part as the result of "welfare reform" and the "reinventing government" initiative that eliminated 426,200 federal jobs, some 25,000 of them through layoffs.

Clinton-era austerity resulted in a federal budget surplus. Republican President George W. Bush's warmaking spending spree after the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, following his tax giveaways to the wealthy, created the federal budget deficit that has since been used as an all-purpose political cover for everything from the federal bankruptcy of the city of Detroit to the layoff of teachers across the U.S., despite overcrowded classrooms existing everywhere.

AND IT’S an international, bipartisan approach, though Democrats utter a few words of protest.

Last February, President Barack Obama decried what he called "mindless austerity", referring to the "sequester,” the result of a 2011 political deal Obama himself made with House Republicans that sanctioned $917 billion in spending cuts over 10 years. When a congressional commission failed to agree on further reductions, automatic cuts worth $1.2 trillion through fiscal year 2021 kicked in.

What would Obama prefer? It would be best called "mindful austerity." That, after all, was his response to the worst economic crisis since the Great Recession.

The "mindful" part was the $700 billion Trouble Asset Relief Program and a $1.2 trillion bailout of the big banks through the Federal Reserve's zero-percent interest rates and emergency lending. That kept the financial system running and appeased Corporate America, even if working people were left to bear the brunt of home foreclosures and mass, long-term unemployment.

Today, the bank bailout and sequester have faded from the news amid happy talk about the expanding U.S. economy. A series of short-term legislative fixes have blunted the sequester's impact in some areas. Notably, the Pentagon has been able to use the U.S. foreign policy debacle in Iraq to boost military spending because Congress put the money into war-fighting budgets that are exempt from the cuts.

Those in need of decent social spending don't have nearly as many friends in Congress or the White House. According the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, "measured in constant 2016 dollars, the 2015 cap on non-defense appropriations is $94 billion, or 16 percent, below the comparable 2010 level." If the trend continues, the share of overall non-defense spending as a percentage of GDP will be the lowest since 1962—before the Great Society programs such as Medicare and Medicaid were enacted.

Obama, whatever his rhetoric, is not an opponent of such austerity measures. He is their enabler. He came into office offering a "grand bargain" to Republicans that involved a tax increase on the rich in exchange for "entitlement reform"—that is, cuts to Medicare and Social Security. Obama tried to avert the sequester not by appealing to popular support, but by offering a staggering $3 trillion cut in federal spending in exchange for $1 trillion in tax increases.

AUSTERITY AT the federal level is the backdrop for rolling crises that have affected states and cities across the U.S. since the economy began to tank in 2007. Between January 2009, when Obama took office and early 2014, some 734,000 public sector jobs were lost, including 250,000 teachers.

Some states and regions have benefited from the ongoing economic rebound—most notably, California, the center of the technology boom, where there's now an acute shortage of public school teachers.

In most of the country, however, the U.S. economic recovery—the weakest since the 1930s—has been too anemic to generate the type of tax revenues needed to fund basic social services. Some 30 states collect less in taxes today than they did in 2007, when the recession began. As the Wall Street Journal reported, "States are left debating how to pay for schools, health care and public safety, and whether belt-tightening measures sparked by the recession will remain even as the economy shows signs of growing strength."

That was the backdrop for the city of Detroit's bankruptcy proceedings. The city, of course, was hit not only by the Great Recession, but 40 years of disinvestment by auto companies that closed plants in favor of new ones that didn’t have the militant, disproportionately African American workforce that shook the industry in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The pullout of industry led to a collapse of population to 680,000, less than half of the city’s 1950s peak. This inevitably drained the city of tax revenue.

Thus, the majority Black and impoverished city became a test-bed for all manner of neoliberal social policies that would be familiar to anyone in Greece. They include the closure of swathes of Detroit public schools and their replacement with privately run charters, now attended by a majority of the city’s students; the cutoff of water to those behind on their payments; and the creation of an unelected financial review board.

Bankruptcy was the tool used to deliver the next blow. As Detroit-based socialist Dianne Feeley wrote, "[T]he city’s bankruptcy was carried out on the backs of retired city workers. Retirees lost their cost-of-living increases, most of their health care, and took a 4.5 percent pay cut." Feeley noted that if city-initiated evictions for property tax arrears continued, another 100,000 people could be forced out of the city.

THE COLONIAL-style approach to imposing austerity in Detroit has now come to an actual U.S. colony: Puerto Rico.

The island has long used as a social laboratory for big business and the federal government—everything from birth control pills to U.S. Navy target practice on the island of Vieques. Now, Gov. Alejandro García is preparing a Greece-like austerity program so that Puerto Rico can meet obligations on $72 billion in government bonds. García is backed by both Wall Street banks and a trio of economists formerly with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an institution with a long record of imposing cuts in social spending as a condition for loans, as it is doing in Greece today.

A nine-year recession began when Puerto Rico's historic tax advantages to U.S. corporations began to phase out. Corporate America looked around at cheaper alternatives in Latin America and started pulling out, helping to trigger an economic slump that began nearly a decade ago.

As Puerto Rican socialist Daniel Orsini noted, successive governments tried to compensate by cutting social spending, privatizing government assets and attacking public-sector unions. The measures failed to solve the crisis, and the tax base continued to shrink, leading to the closure of hundreds of schools and an 11.5 percent sales tax, higher than any U.S. state. Of all the revenue that gets raised, a big chunk goes to pay down debt.

Now, the ex-IMF officials want to turn the screws even tighter on the island’s 3 million residents. Their plan calls for the elimination of teachers' jobs, cuts in tuition subsidies to the University of Puerto Rico, and cuts in Medicare and Medicaid, for starters.

As Ed Morales wrote in the Nation, "What Puerto Rico has in common with Greece is that it is a peripheral economy that has been invaded by hedge funds and pushed, by speculation and ballooning debt-service payments, to its limits."

EVEN WHEN the economic conditions are nowhere near as severe as Greece, Detroit or Puerto Rico, the default setting of politicians is to use the crisis to either consolidate austerity policies or further them.

Thus, in New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed labor contracts with city unions that fell far short of the pay increases that municipal employees would have gotten had the previous mayor, Michael Bloomberg, agreed to negotiate contracts. Thus, despite the city's Wall Street-led economic comeback, the liberal Democratic mayor succeeded in holding down the rate of increase in compensation for teachers and other city workers, which will affect them for the rest of their working lives in terms of smaller pay raises and pensions.

Similarly, in California, Gov. Jerry Brown, having obtained concessions on public-sector pensions when the recession hit, recently pushed for cuts in health benefits for state workers and retirees.

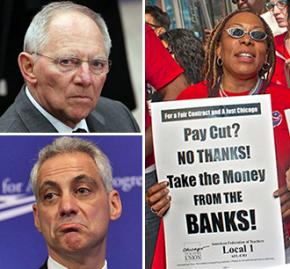

Then there's Illinois, where the economy is considerably weaker than California. Today, Republican hedge fund boss Bruce Rauner sits in the governor's mansion, and an architect of Obama's “mindful austerity,” Rahm Emanuel, has begun his second term as mayor of Chicago.

As White House chief of staff, Emanuel famously said of the Great Recession, "You never want a serious crisis to go to waste. And what I mean by that is an opportunity to do things you think you could not do before.". That included the bankruptcy of General Motors and the slashing of workers' compensation work rules. When United Auto Worker officials complained, Emanuel replied, "Fuck the UAW." The Obama administration then used bankruptcy laws to further Corporate America's goal of slashing wages across the manufacturing sector.

Back in Illinois today, Rauner, a former business associate of Emanuel's, wants to use bankruptcy to achieve something similar in the public sector. The governor has called for bankruptcy proceedings for the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) in order to restructure the district's debt and address a $1 billion deficit. Rauner has stated his desire to see municipalities across the state use bankruptcy to cut deficits and dismantle union contracts.

Rauner's biggest attack is aimed at public employees’ pension liability of $165 billion, which is 40 percent underfunded.

A legislative "fix" for city and state employee pensions, passed by Rauner's predecessor, Democrat Pat Quinn, has been ruled unconstitutional because it would have cut benefits guaranteed by the state constitution. The result is a three-way maneuver between Rauner, the Democratic-controlled state legislature and Emanuel up in Chicago. Rauner has refused to accept a state budget or agree to new taxes to fund pensions and government operations unless and until the legislature agrees to a series of anti-union measures.

Rauner has also vowed to link approval of a $480 million budget request from Chicago Public Schools for teachers' pensions to measures that would dramatically weaken the collective bargaining rights of the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU).

Rauner declared, "The people of Chicago, the voters of Chicago, the mayor of Chicago, the school board of the Chicago Public Schools should be enabled to decide what gets collectively bargained and what doesn’t so they don’t end up with the teachers union having dictatorial powers, in effect and causing the financial duress that Chicago public schools are facing right now."

Most of the state’s unions are looking to the Democrats to shield them from Rauner. But it’s a doomed strategy. It was the Democrats, after all, who legitimized the attack on pensions. For example, former Gov. Quinn also refused to pay workers a raise that he had negotiated on the grounds that the legislature didn't fund it. Even the CTU joined other unions in backing Quinn despite his anti-union policies. But Quinn's union-bashing has only made it easier for Rauner to go on the offensive against labor.

IN REALITY, Rauner and Emanuel are carrying out a classic good cop/bad cop routine, with Emanuel claiming to be a defender of Chicago working people and organized labor, while Rauner swings the ax.

But Emanuel isn't getting away with it, having shown his hand during negotiations over a new contract for the CTU. The mayor's demand that teachers pay for a portion of their pensions amounts to a 7 percent pay cut. His strategy essentially dovetails with the Rauner agenda. CTU President Karen Lewis responded by stating that the issue could lead to a strike. It would be the second such clash—a rematch of the 2012 showdown in which the union bested the mayor by walking off the job and mobilizing overwhelming popular support.

The attack on teachers and public education is just one element of the Emanuel austerity program, imposed in the wake of past decisions to raise city funds through privatization and borrowing, while refusing to tax corporations and the wealthy.

That problem is exacerbated by the fact that the big banks have saddled CPS and the city with toxic interest rate deals and penalties that come with downgrades of bond ratings. As Saqib Bhatti, director of ReFund America, wrote in In These Times, "But as was the case in Detroit, the talk of a Chicago bankruptcy has little to do with the city’s financial health, and much to do with a broader political agenda to obliterate the social safety net and slash pensions."

That's why the 2012 CTU strike was so important. By fighting not just for teachers' livelihoods, but also raising the issues of apartheid schools and social inequality, the labor battle became a touchstone for the wider struggle against austerity and big-business drivers of an anti-worker agenda. Now the battle lines are being drawn once again.

The same dynamics are playing out in San Juan and Athens. While the struggle against austerity will have its specific targets in every locality, there are clear and increasingly obvious connections that unite the battles. And the sharper the conflict, the more broadly questions are raised about the priorities and direction of society.

Today's movements challenging neoliberalism, austerity and racism can draw inspiration from Martin Luther King's efforts to generalize the struggle for social justice near the end of his life.

Although the movement for civil rights and voting rights in the South had prevailed by 1965, King continued the fight for poor people and workers—he was assassinated in 1968 while in Memphis as part of a support campaign for a strike of Black sanitation workers. As he said in a famous 1967 speech:

And one day we must ask the question, "Why are there 40 million poor people in America?" And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising questions about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth. When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy. And I'm simply saying that more and more, we've got to begin to ask questions about the whole society.

We are called upon to help the discouraged beggars in life's market place. But one day we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring. It means that questions must be raised. You see, my friends, when you deal with this, you begin to ask the question, "Who owns the oil?" You begin to ask the question, "Who owns the iron ore?" You begin to ask the question, "Why is it that people have to pay water bills in a world that is two thirds water?" These are questions that must be asked.